Toledot is the Birth and Geneaology of Heaven and Earth

Toledot, this week’s Torah portion, is the story of birthings—movements from disorder into new creation. While often translated as genealogy, history, or account, the word goes much deeper: it means to bring forth children, to beget, to travail. It is the language of covenant and creation, of life produced when two realities meant to be one finally join together.

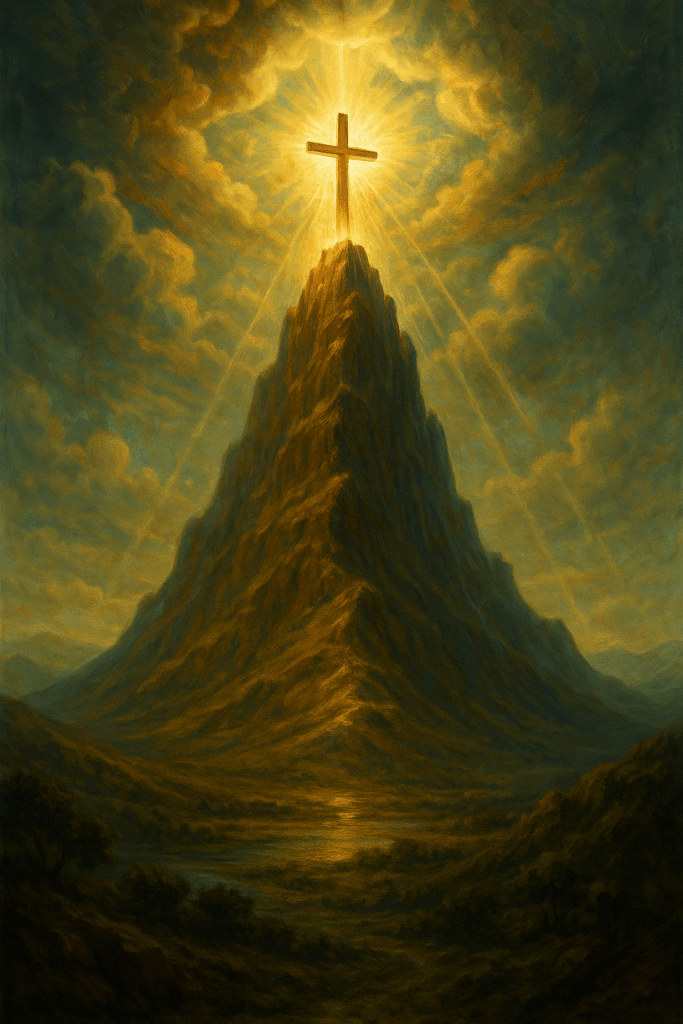

The first toledot in Scripture is not human at all. It is cosmic: “These are the toledot of the heavens and the earth…” (Gen. 2:4). At first glance this seems odd. How can heaven and earth give birth? But the text is hinting at a profound unity—almost a marriage—between God’s realm and humanity’s realm. What their union produces is creation itself.

Heaven, God’s domain, and earth, humanity’s domain, are meant to function as one integrated space. That has always been the goal of the biblical story: heaven and earth reunited so that the “sons of God” can be birthed—the ones who inherit and steward creation toward its intended flourishing. Two spaces brought together in unity, producing a people who bear God’s image and bear His authority.

Sacred Marriage

Creation is presented as a marriage, a sacred joining, where God’s space touches ours and life emerges in harmony. And Scripture keeps telling this story over and over again: heaven and earth were designed to be partners, destined for full union, destined to dwell together as they once did in Eden.

Revelation completes the loop with the same theme: a new heaven and a new earth, no longer two realms, but one restored marriage. What began in Genesis as creation ends in Revelation as new creation—the full maturity of God’s project. And between these two bookends lies the struggle: a fractured world, a divided cosmos, two kingdoms at war—Yahweh and the serpent, order and chaos, covenant and anti-covenant. Nowhere is this conflict more clearly seen than in the Torah portion Toledot, with the tension between Esav and Jacob.

Isaac and Rebekah

This is where Isaac and Rebekah enter the story. We expect toledot to begin with Isaac and a list of his children, but the text surprises us: “Abraham begot (yalad) Isaac.” Isaac is sixty when Rebekah bears the twins, and forty when he marries her. The sequence reminds us that Isaac can bring forth life only because Abraham first brought forth him. Covenant flows forward through sons; the story continues because someone was born.

But Rebekah, like the matriarchs before and after her, is barren. Barrenness in Scripture is never just biological. It is symbolic of primordial chaos—the unformed, unproductive void before God speaks in Genesis 1. A barren woman embodies the de-created world. So when God opens her womb, He is not simply providing a child; He is enacting new creation. This is why the births of Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Samson, Samuel, and John the Immerser all come through barren women. Every one is a living signpost pointing toward the ultimate new creation: the birth of the Son of God, the true heir, the new Adam.

Rebekah conceives, but the struggle is far from over. In fact, it is just beginning. The Hebrew word used for the twins “struggling” means to crush, be crushed, or oppress. What is happening inside her womb mirrors the cosmic conflict outside it.

Two Kingdoms in Conflict

Two nations. Two kingdoms. Two destinies locked in prenatal combat. “Two goyim are in your womb…” Not merely sons but nations, peoples, worlds, futures. “Two peoples shall be separated…” The word means to divide by breaking apart.

Then the great reversal: “The many, the great, will serve the little, the small, the insignificant.” The unlikely heir becomes the true ruler. The younger becomes the leader.

This is the kingdom pattern from beginning to end—Micah’s ruler born in tiny and insignificant Bethlehem, Isaiah’s “least becoming a thousand,” Yeshua choosing fishermen instead of princes. This is the toledot pattern: God bringing forth what the world does not expect. “But you, Bethlehem Ephrathah, though you are little among the thousands of Judah, from you shall come forth the Ruler…”

Israel, the small nation, prevails and continues to prevail despite the vastness of empires around her. Logic says she should not exist. Scripture says she exists because God brings forth life from unlikely places.

Genealogies and New Creation

The Bible’s story is held together by these birthings—the toledot of the heavens and the earth, the toledot of Adam, the toledot of Noah, the toledot of Abraham, the toledot of Isaac, the toledot of Jacob, and finally the toledot of Yeshua the Messiah. Matthew opens with this line: “The book of the genesis (toledot) of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.” The story loops back to Abraham, then forward to the new humanity.

And the birthings are not over. Toledot is still happening. We are living in the long stretch between creation and new creation—between promise and fulfillment. And the rhythm remains unchanged: new life out of barrenness, order out of chaos, kingdom rising through the unlikely. God is still bringing forth children, still writing toledot, still moving heaven and earth toward unity—one new birth at a time.

Leave a Reply